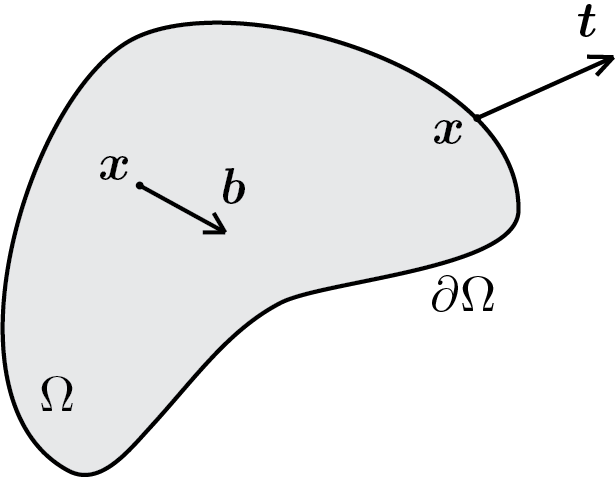

The mechanical interaction between parts of a body or body with the surrounding environment is described by means of forces. Two types of forces are considered: volume forces, which act within the body, and surface forces, which are exerted through a surface. For the hypothesis of continuity, as done for the mass, also the forces are postulated through the existence of vector fields that allow to calculate the resultant of all the forces acting on the body

\begin{equation}

\func{\vec{R}}{\body} = \int_{\body} \vec{b} \, dv + \int_{\partial\body} \vec{t} \, ds \,,\tag{2.1.4}

\end{equation}

and the resultant torque, with respect to the origin, of the applied forces

\begin{equation}

\func{\calvec{M}}{\body} = \int_{\body} \vec{x} \times \vec{b} \, dv + \int_{\partial\body} \vec{x} \times \vec{t} \, ds \,.\tag{2.1.5}

\end{equation}

where \(\partial \body \) is the boundary of \(\body\) and therefore it is a surface, \(\vec{b} \) and \(\vec{t} \) denote two vector fields which will be better described below and which represent, respectively, a bulk force density or, simply, the bulk force and a surface force density that will be called traction.

Subsubsection 2.1.3.2 traction

Traction comes from physical contact between bodies. Contact can take place through

\(\partial \body \text{,}\) the boundary of the body, and in this case there will be an

external traction. Or, as we will discuss more extensively in the following sections, it can take place through an ideal surface passing inside the body, in this case we will speak of an

internal traction. We therefore introduce a formal definition of traction which will allow us to specify the dependence of this vector field.

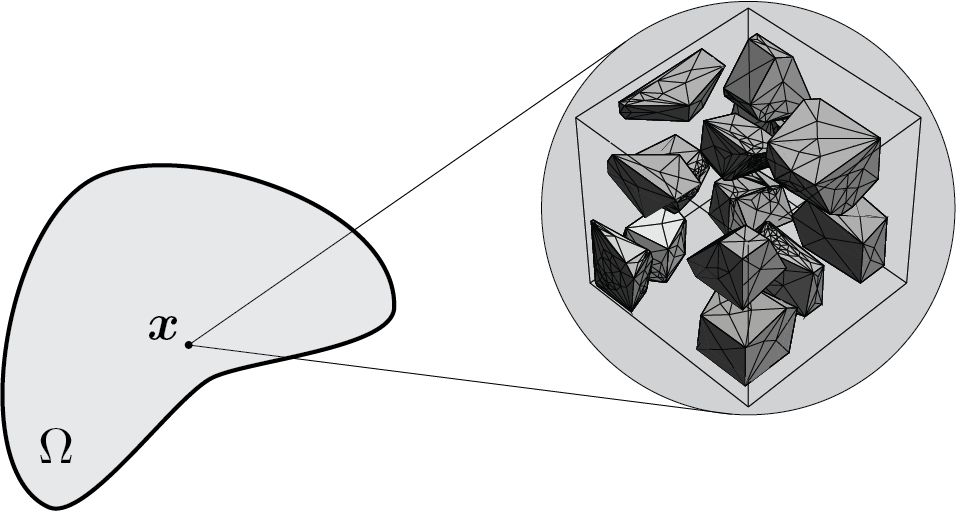

Given a point \(\vec{x} \) of the body placed inside or on the border of \(\body \text{,}\) and given a family of surfaces \(\func{\Gamma_{\delta}} {\vec{x}} \) passing through this point such that \(\func{a} {\func{\Gamma_{\delta}} {\vec{x}}} = \int_{\Gamma_\delta} ds \rightarrow 0 \) if \(\delta \rightarrow 0 \text{,}\) we assume the existence of a vector field \(\func{\vec{t}} {\vec{x}, \Gamma_{\delta}} \) defined as follows

\begin{equation}

\func{\vec{t}}{\vec{x},\Gamma_{\delta}} = \lim_{\delta \to 0} \frac{\func{\vec{F}}{\func{\Gamma_{\delta}}{\vec{x}}}}{\func{a}{\func{\Gamma_{\delta}}{\vec{x}}}} \,,\tag{2.1.7}

\end{equation}

where \(\func{\vec{F}}{\func{\Gamma_{\delta}}{\vec{x}}}\) is a surface force acting on the area \(\func{\Gamma_{\delta}}{\vec{x}}\text{.}\) \(\func{\vec{t}}{\vec{x}, \Gamma_{\delta}}\) is called traction vector, or simply traction, depending on the position \(\vec{x}\) and on the family of surfaces passing through \(\vec{x}\text{.}\)

A suitable definition of this dependence, elaborated by Cauchy, leads to the notion of

Cauchy stress tensor.